The tech world has been buzzing this summer over the new wave of giant, AI acquihire deals in which a large technology company—Google, OpenAI, Meta—spends billions to acquire a startup’s key executives, and often some intellectual property, but leaves the rest of the company behind.

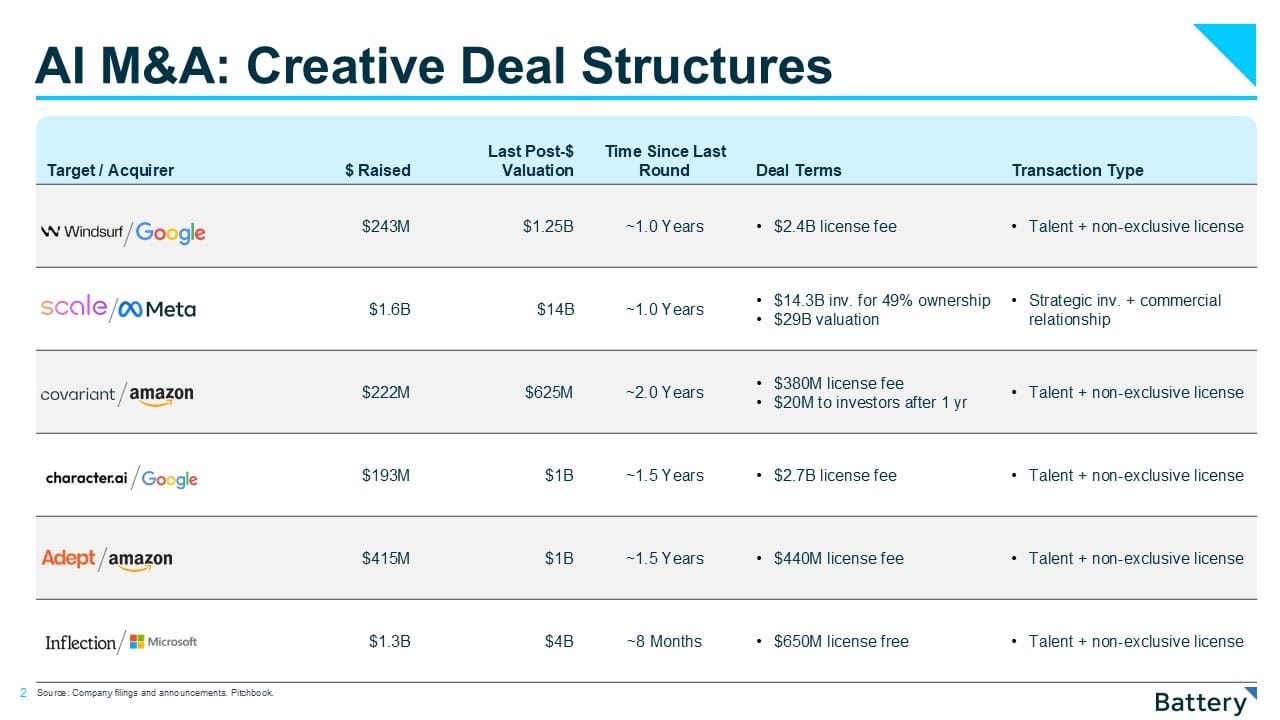

The most notable example is Windsurf. The promising AI company was set to be acquired by OpenAI, but then Google swooped in and paid $2.4 billion for a few senior executives and a technology license. But this wasn’t the first instance of this new tech-deal structure. We have now seen it executed at least five other times in the last two years, and the whisper in the industry is that other companies have been approached about similar tie-ups.

The details of these deal dynamics, and their impact on company employees and investors, have been hotly debated in the press and on social media. But it’s worth exploring why this new wave of AI M&A is happening—and how conditions need to evolve for tech M&A to get back to normal. Put another way: When will big tech acquirers start buying AI companies not just for their teams, but for their durable business moats?

To be sure, traditional M&A is still happening: Google is in the process of closing its $32 billion acquisition of Wiz, for example. But it’s instructive to compare that deal to the Windsurf transaction. The latter company was a legitimate contender in the AI coding space, a category proving to have one of the strongest signs of product-market fit. The company was growing quickly, hiring aggressively, and had real enterprise customers.

So why didn’t Google want to acquire the whole thing? In our view, it likely comes down to two factors: 1) The incredibly rapid pace of innovation in AI, which is faster than any previous technology wave we’ve seen, and 2) the scarcity of top-level talent to run cutting-edge AI businesses today. When those dynamics change, and more-mature companies with deeper competitive moats (and more skilled executives) develop, we will likely see a return to pre-AI M&A trends.

From eyeballs to AI research teams

Our overall belief is that the current wave of Windsurf-like, talent-license deals are a clear indicator of how early we are in the AI cycle. During the dot-com bubble of the late 1990s and the early mobile era of the 2010s, M&A was often valued based on “eyeballs” and talent that could drive distribution. Today, these deals are valued based largely on the caliber of a company’s elite research team, not enterprise value. The frontier of AI is still being pushed by labs and research teams with immense talent density. Maturation will come from two primary sources:

- Deeper vertical integration: As startups move from being thin wrappers around foundational models to becoming “fat applications,” they will build more defensible value. This involves owning more of the stack, from data ingestion and processing to model fine-tuning and deployment. For example, companies like Cursor have built their own models for certain features, like Tab, that far exceed the outputs from the AI labs. Meanwhile, Sierra continues to push how much infrastructure it can own by building its own agent-orchestration framework to optimize inference across its system. As companies own more proprietary aspects of their respective stacks, value will accrue to their unique IP.

- Uncovering the new interaction layer: Many AI-native applications today are built within the UI layers of existing systems and applications. Where people do work, where they orchestrate agents or interact with AI systems will matter in the future, and unlocking this new layer of engagement will matter as well. As we shift from innovating at the infrastructure layer to the application and UI layer, we will see the change in which value accrues among companies as well.

The coming democratization of AI talent

The current deal structures are a direct reaction of an incredibly competitive AI labor market for a small pool of elite AI researchers and AI-native builders. These individuals are seen as non-reproducible assets, making their acquisition the primary goal in M&A. When technological breakthroughs depend—as they do in AI today—on novel techniques in data labeling, training, compute optimization, and model architecture, the value in these techniques resides in the talent that can produce these outcomes, not necessarily the outcomes themselves.

As AI development becomes more democratized through innovation, the open-source ecosystem, and standardized platforms, the acute scarcity of top-tier talent will lessen. When a team is no longer a rare commodity that can only be acquired whole, the rationale for talent-centric deals will fade. Value will shift back to the company as a holistic entity: a collection of talent, technology, and market traction. While the talent game will likely dictate the market for the next 12-24 months, the democratizing force of AI will ensure that speed of progress and slope of learning will always outpace the sheer volume of talent at any single organization.

Build a moat

Product moats today are fleeting, as the pace of AI innovation far outpaces any single company’s ability to create lasting defensibility. For strategic M&A to flourish, acquirers need to see durable competitive advantages worth buying. It is not that tech giants are unwilling to make large, strategic acquisitions. In addition to Google’s planned acquisition of Wiz–a prime example of an acquisition made for the traditional reasons of superior tech, talent, and traction—Databricks* has been an active acquirer recently, buying MosaicML for $1.3B, Tabular for $1B, and Neon for $1B. Databricks has integrated these key assets to build a comprehensive data intelligence and AI platform.

These deals were justified by the targets’ strategic value, not just their talent. We believe AI-company moats will evolve in one or more of the following areas in the coming years, helping these startups become more viable acquisition candidates:

- Proprietary data: Companies with unique, high-quality data that creates a feedback loop will help improve AI models in a way competitors cannot replicate.

- Distribution & network effects: A large, engaged user base makes the product more valuable as more people use it.

- Workflow integration: Deeply embedding an AI tool into a critical business process makes it difficult and costly for customers to switch or meaningfully changing the outcome of a business process. This makes the product “sticky” and boosts revenue.

The path forward

The structures influencing the market today will inevitably change. While talent-licensing deals offer speed, they lack certainty for the ecosystem. The rise of private-to-private M&A, led by companies like Stripe (which acquired stablecoin platform Bridge for $1.1B) and Databricks, is a positive signal, indicating a healthy market where growing companies acquire others for strategic capabilities.

Furthermore, the governance structures between founders and investors will likely evolve, with greater scrutiny placed on key-person clauses and terms that could trigger a premature liquidity event (i.e., does a non-exclusive license trigger protective provisions for investors?). These hybrid structures are inherently flawed, in our view, as they can erode trust. But with the stakes involved, they represent a workaround that will likely make its way into the ecosystem. The real sign of a maturing market will be when acquiring a company is once again about buying a kingdom, and not just hiring its court.

The information contained here is based solely on the opinions of Danel Dayan, and nothing should be construed as investment advice. This material is provided for informational purposes, and it is not, and may not be relied on in any manner as, legal, tax or investment advice or as an offer to sell or a solicitation of an offer to buy an interest in any fund or investment vehicle managed by Battery Ventures or any other Battery entity. The views expressed here are solely those of the authors.

The information above may contain projections or other forward-looking statements regarding future events or expectations. Predictions, opinions and other information discussed in this publication are subject to change continually and without notice of any kind and may no longer be true after the date indicated. Battery Ventures assumes no duty to and does not undertake to update forward-looking statements.

*Denotes a Battery portfolio company. For a full list of all Battery investments and exits, please click here.

A monthly newsletter to share new ideas, insights and introductions to help entrepreneurs grow their businesses.